Personality models and personal development

Part 3 of a series on personal development in coaching

In the first part of this series of posts, I summarised the primary task of personal development as getting to know and mastering our personality, through exploring all levels of our consciousness. I also like the phrase our Italian psychosynthesis partners (IIPE) use to describe personal development: “know yourself, accept yourself, transform yourself”. This undertaking, both for ourselves and in support of our clients benefits from having some good maps of the territory. My aim in this third post on this topic, is to overview some useful models of the personality as well as to contribute something new that might be of value to coaches. At the same time, we must remember that any maps are simply there to support the real work of exploration and discovery taking place at the individual level in coaching and other personal development activity. As much as possible I will illustrate how to apply the models using the example of my own personal development journey.

I start with Jung’s personality typology and Assagioli’s psychological elements, which together provide a fairly comprehensive overview of the territory of the personality. I then introduce some of the better-known tools for identifying personality issues, before working towards my own model of psychological health that combines (i) individuation – how we are in our relationship with others, with (ii) self-sense – how we are in our relationship with ourselves. It is important to remember that our interest is in exploring the territory of what we call healthy neurosis here rather than pathology, so our perspective is rather different to that of conventional psychology or psychotherapy.

Jung and Assagioli – personality type and psychological functions

The most common approaches to describing or analysing personality are type and trait theories, of which I will focus on the theory of psychological types developed by Carl Jung, which has been used as the foundation for some of the most commonly used psychometric profiling tools in organisations, including the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), Insights and DISC.

For those of you who are not familiar with the Jungian typology, below is a very basic summary taken from material I was given on my MSc CASS in the 90’s (original source unknown, apologies):

The Jungian typology is concerned with individuals’ preferences for four cognitive activities and provides a dichotomous scale for each of these activities as summarised below:

Where you focus your attention – Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I)

The way you take in information – Sensing (S) or Intuition (N)

The way you make decisions – Thinking (T) or Feeling (F)

How you dealwith the outer world – Judging (J) or Perceiving (P)

People will tend to have a preference towards one or other end of the scale for each of these four scales, which creates 16 different basic combinations or typologies. Each of the 16 types will tend to be associated with different leadership characteristics and styles. If you have completed a Myers-Briggs (or similar) questionnaire and received your profile, you should know what your Jungian typology is (e.g. ESTJ or INFP).

There are many ways and places to find out more about any of the various flavours of the Jungian system and to generate a profile as a way of getting to know yourself better (e.g. free online at personalitymax, or for a fee at discover your personality, or with Insights or DISC, etc). As with most psychometric tools, I find them both frustrating and intriguing in equal measure; frustrating because of the binary way they are presented, often asking you to make choices between seeming opposites, whereas just as often I find the answers are ‘it depends’ or ‘neither’, as opposed to one or the other. At the same time, there is a value to profiling that comes from the self-recognition and identification with a type or types which allows you to see yourself more clearly for who you are and how you are, as well as how others who are not your type(s) are different. Although I would not discourage you or your clients from using such tools, rather than getting too hooked on identifying with a type (e.g. I am 7 and 5 on the Enneagram!), I would encourage you to use them more qualitatively, creatively and flexibly to explore yourself in different ways. For example, asking yourself: in what ways am I introverted and in what ways am I extroverted? What might it mean to recognise my feeling nature more? In what way might I be suppressing my feeling and limiting my emotional intelligence? What are the implications of my seeming bias towards intuition over sensory information as my source of information about the world?

Jung’s popularised the trait of extraversion-introversion as a dimension of human personality, although unfortunately it’s use in popular psychology has become distorted into binary types – e.g. are you an introvert or an extrovert, do you like to stay in and read a book or go out to socialise? To quote Wikipedia on this:

Carl Jung and the developers of the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator provide a different perspective and suggest that everyone has both an extraverted side and an introverted side, with one being more dominant than the other. Rather than focusing on interpersonal behaviour, however, Jung defined introversion as an “attitude-type characterised by orientation in life through subjective psychic contents” (focus on one’s inner psychic activity) and extraversion as “an attitude type characterised by concentration of interest on the external object” (focus on the outside world).[3]

Assagioli also saw introversion and extraversion as useful primary ways of exploring and mapping our personality, for example:

As Jung pointed out, an individual may be both introverted and extraverted according to the different psychological functions; for instance, introverted in the feeling function while extraverted in the thinking function (Assagioli, 1965, p148)

I find this attitudinal perspective more useful than the now common behavioural focus. As a coach, what do I notice most about the people I am coaching from a psychological or personality perspective? I notice the extent to which they are focused on their inner world and their outer world and whether they are able to include and move between the two. And I often encounter clients at both extremes – either where they are so preoccupied with the outer world of doing, with concrete goals and achievement that they find it hard to articulate their inner world – or they are so caught in their inner world that they find it hard to link personal development to observable and measurable achievement and progress in their lives or work. The former situation is more common in leadership coaching with successful leaders who are outer-oriented and reluctant or unable to explore their inner world.

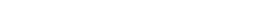

Assagioli drew upon Jung’s theory of psychological types and added depths and dimensions with his own model of psychological functions. Jung considered there to be four primary psychic functions: sensation, feeling, thought and intuition (250, 1974), to which Assagioli adds imagination and impulse or desire and importantly places the will and the self at the centre of psychological functioning.

This gives us a map we can work with more dynamically as coaches, with a focus on supporting the healthy engagement and expression of will through mastery of the psychological functions.

Personality issues and edges

FIRO-B is often used to complement Jungian types, with its’ focus on relational preferences; in terms of our needs to express and receive inclusion, control and affection. This can indirectly point towards potential issues to work on, for example where our need to exert structure and control is much greater than our acceptance of structure or control from others (as is the case for myself), but this still needs to be combined with other work such as in coaching in order to personalise the meaning.

I sometimes use a TA Stress Drivers questionnaire as a quick way to help a coachee identify psychological patterns and edges to work on. The five stress drivers are: be perfect; please others; hurry up; try harder; be strong – the great thing about these is that they are easily recognisable in ourselves and that everyone will have their own unique stress drivers profile. They also combine well with subpersonalities and mindsets approaches to working with clients. My very strong ‘Hurry Up’ driver, for example is associated with both my ‘rebel’ authority-rejecting subpersonality and my mindsets about never having enough time.

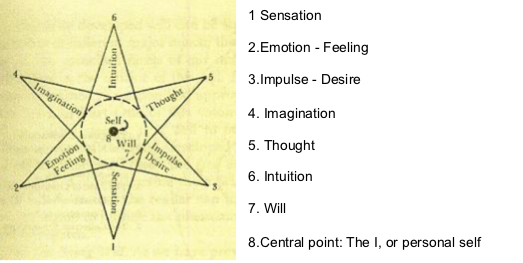

Another approach I have drawn upon is the Gestalt cycle of experience, which indicates pathologies that can occur if healthy completion of cycles of experience are interrupted for an individual (also true for an organisation). We will tend to form patterns of behaviour in the way that we don’t work through complete cycles of experience, and you might recognise points along the cycle below where you get caught and fall into a pattern. For a proper introduction to Gestalt and the cycle of experience within an organisational context I refer you to a resource I have made available on our website here.

For example, I tend to get caught at the point of contact in the cycle of my engagement in the world and instead of ever achieving satisfying resolutions, I am onto the next thing that mobilises my energy. Recognising this has led me to focus on the need to contain and allow experiences, projects or situations the time and space to come to fruition. I have also increased the attention I give to the start of the cycle – sensationand awareness, and my ability to respond appropriately to needs arising in my consciousness (whether inner or outer in origin) rather than reacting out of habit or outdated patterns.

There are also a number of ‘derailer’ type approaches (such as Hogan derailers) which highlight the ways in which leaders trip themselves up through unconscious and unexamined aspects of their personalities (derailers). I have used these on occasion with uneven success, although I know many leadership coaches who find these tools a very useful way in to working with the unconscious or shadow side of their clients.

Towards a model of psychological health for coaching

In search of a more accessible map to explain our personality edges or distortions, I turn towards the work of Manfred Kets de Vries (2014) and others who have applied the body of material about attachment theory (following psychoanalyst John Bowlby) to the field of work organisations and leadership. He suggests that many people including highly successful leaders and professionals, develop dysfunctional attachment patterns in early life which “in later life lead to repetitive patterns of unhealthy thoughts and conflictive relationships”. He goes on to describes how:

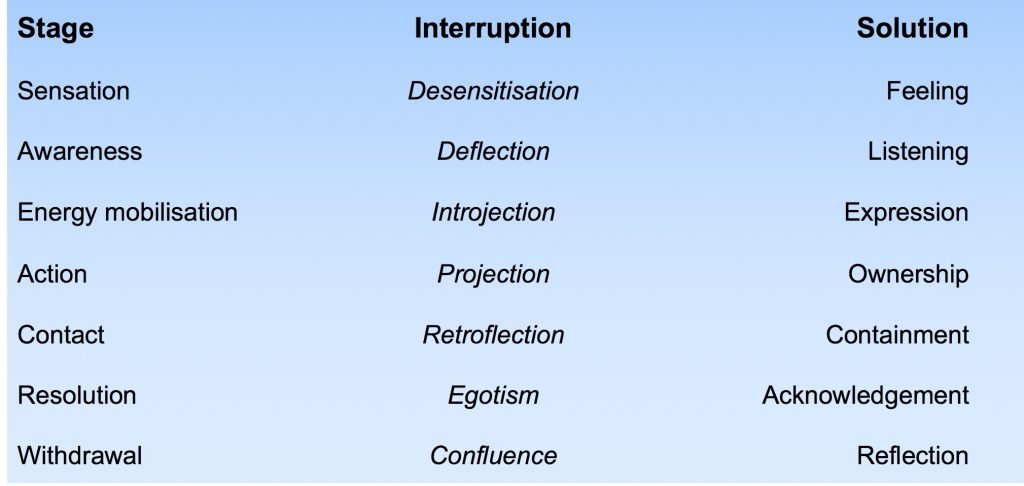

More recent works on attachment behaviour propose four attachment styles based upon two dimensions: the anxiety dimension – which focuses on the anxiety we may feel about rejection and abandonment – and the avoidant dimension – which reflects the discomfort associated with closeness and dependency”.

The graphic below is my attempt to illustrate this, drawing upon Kets de Vries’ paper:

Gervase Bushe tackles similar territory by talking in terms of self-differentiation patterns, contrasting extremes of fusion and disconnection, which are associated with separation anxiety with suffocation anxiety respectively. The Fusion polarity is characterised by too much connection, a lack of boundaries and an over-dependence on what other people think or experience. The Disconnection polarity tends towards keeping separate, through maintaining rigid boundaries and not thinking about what others are experiencing (Bushe p80). Bushe goes on to describe the ideal of self-differentiation where we are separate but connected, have choices about boundaries and how we react to others in interactions and want to know what others are experiencing but stay true to our self.

I have added the key terms used by Gervase Bush, separation anxiety and suffocation anxiety on the graphic of Kets de Vries’ model. On balance, I prefer the language used by Bushe and will adopt his model of self-differentiation going forwards as one axis of my overall model of psychological health, i.e. individuation and how we are in relation to others. Bushe’s Clear Leadership (2010) is the best book I have come across at explaining important psychological ideas in a way that is accessible to the organisational world and I recommend reading it to leaders, coaches and OD professionals alike.

The psychosynthesis triphasic model of development (developed by Joan Evans and Jarlath Benson, see Simpson and Evans, p21 2014) provides a more detailed and nuanced road map for coaches working to support the differentiation and individuation process. It shows how we are all evolving from fusion, to symbiosis to differentiation at three nested levels – building a strong enough ego, a healthy independent sense of I (as in Bushe’s model) and an emergent higher Self. This model is taught on some advanced training programmes in psychosynthesis and we are currently exploring how to apply it more explicitly to coaching.

The second axis of my model of psychological health concerns how we are in our relationship with ourselves – our self-orientation or self-sense. One way to think about this dimension is in terms of three separate but inter-related aspects of self-relationship: self-esteem, self-acceptance and self-confidence.

From Wikipedia: Self-esteem “reflects an individual’s overall subjective emotional evaluation of his or her own worth… it is the decision made by an individual as an attitude towards the self. Smith and Mackie (2007) defined it by saying “The self-concept is what we think about the self; self-esteem, is the positive or negative evaluations of the self, as in how we feel about it.”[2]:107”.

Rational Emotional Behavioural Therapy advocates self- (and other-) acceptance as a healthier and more useful alternative notion to self-esteem. Self-acceptance is an easier and cleaner attitudinal muscle for the coach to help the coachee focus on than self-esteem, which has the potential to activate unconscious judgements and criticisms, whether about self of others. In this way, practising self-acceptance (and holding compassion for yourself) can be seen as an antidote to low self-esteem.

Self-confidence can be seen as an outcome or consequence of self-esteem and self-acceptance. As coaches, we are more overtly focused on self-confidence in terms our coachees willingness and ability to act and take steps towards their goals. Coaching is intimately concerned with building self-confidence for the coachee over time and the coach is probably holding some awareness of their clients’ self-confidence much of the time they are working together.

Low self-esteem is increasingly common in a world in which we are judging or comparing ourselves to others both consciously and unconsciously in different ways much of the time. Ego-inflation or excessive self-esteem is less common in the general population but is not unusual in very senior and successful leaders. Most of us as coaches and the people we find ourselves coaching are likely to lean towards the low side of self-esteem or self-confidence. Much of the time in coaching what we call healthy neurotics, we are working with a small or large deficit of self-esteem, self-acceptance or self-confidence or all three. Sometimes you may find this needs working on directly and explicitly, at other times the experience of exercising and developing the Will and the achievement of stretch goals naturally builds self-confidence.

The ego-inflated leader is less likely to ask for coaching in the first place. The more extreme the case of inflation, the more likely it is to be holding a shadow of insecurity and low self-esteem that often appears on the rebound (what psychoanalysts call negative inflation). The relationship between ego-inflation and narcissism is complex and although they often come together, they can also be found separately. The topic of the narcissistic leader is important if you are working with the most senior leaders and is explored fully by Kets de Vries in his excellent “Leader on the Couch” (2012).

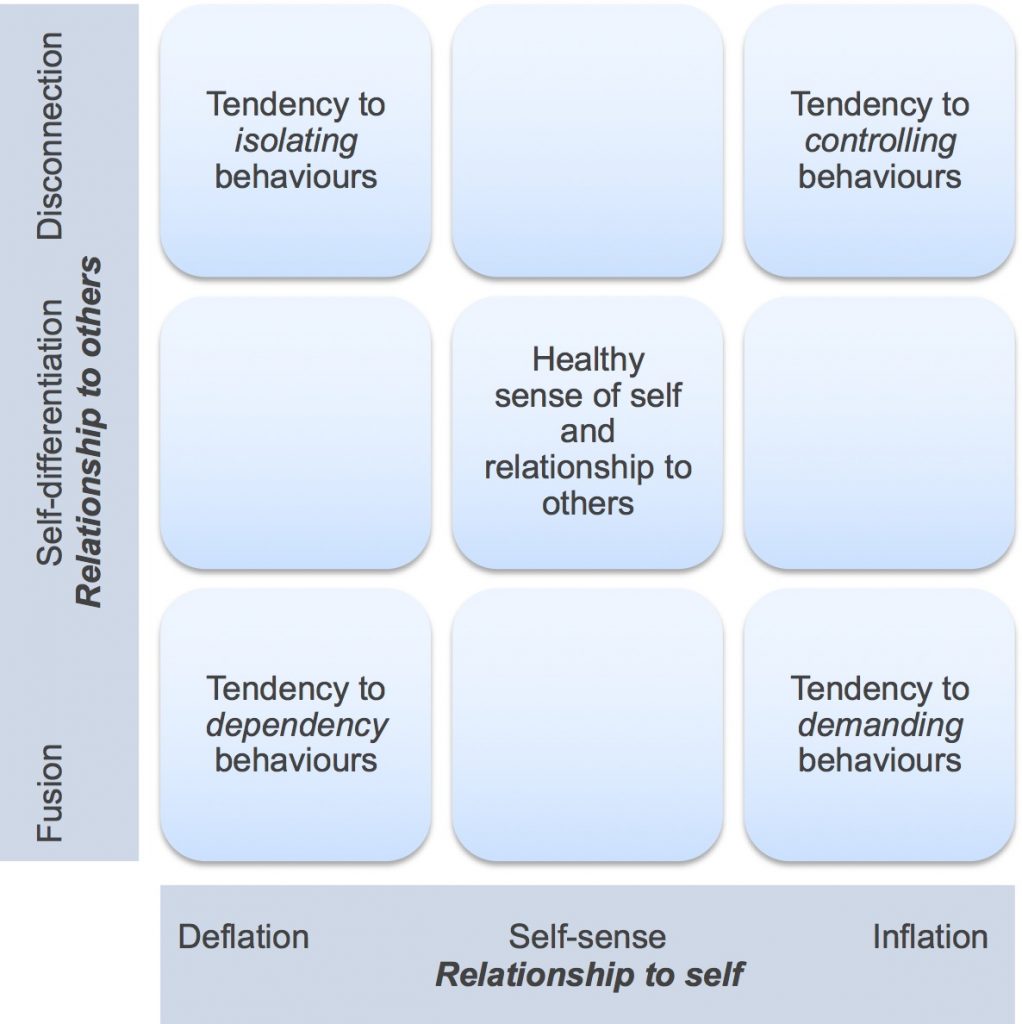

I am not trying to present myself as an expert on these psychological concepts and there are sources and courses where you can go to build a deeper understanding of them. My purpose here is to provide an overview of the territory and introduce useful concepts for you to work with as a coach in relationship to yourself and the people you are coaching. The point here is to be able to recognise general personality types, leanings and inclinations that help us get to grips with the psychological issues and edges we need to work with in personal development. With this in mind, I will now put the two dimensions together, our relationship to ourselves and our relationship to others, giving us this model of psychological health:

The model is dynamic in a number of ways which can’t be easily depicted in a two-dimensional graphic.

- We are interested in a person’s pattern in relationship to each axis, not just their relative position on a scale. For example, is there a pattern of movement, swings from one extreme to another, or a relative stability at one place along the axis. Kets de Vries’ attachment model shows the possibility of the Fearful-Avoidant pattern, in which an individual is caught in a tension between the polarities of Fusion and Disconnection (e.g. they desperately need people’s approval but at the same time feel suffocated by them).

- In relationship to self, the pattern of swinging between deflation and inflation is relatively common and familiar. In extremes this might take us into the territory of the bi-polar disorder, however, many people experience swing patterns without being bipolar. For many, self-esteem can be seen to be contingent on stimulus and events, leading to a “boom or bust” pattern. We can swing from one polarity to another, for example from feeling energised and purposeful to empty and despondent, but rarely resting in a centred or grounded place between the two. This can be compounded by the stresses, pressures and anxieties we experience in our lives and work, which can make us feel like we are always trying to get somewhere rather than be where we are. This describes a common phenomenon that I recognise both for myself from certain times in my life, as well as in some of my coachees, which I will call the ‘missing middle’. This can lead to working on finding our centre, our ground of being, a place less contingent on the events and outcomes of our daily life. We expand on this theme again below.

- The two axes or dimensions are related and inter-dependent in ways that we won’t be able to fully explore here. In other words, the nature of our relationship with others is both informed by and informs the nature of our relationship with ourselves. As a coach, you might intuitively decide which axis needs to be worked on as the priority and then over time, observe how this work brings about progress on the other axis.

- I have indicated in the four corners of the model, examples of behavioural tendencies that you might observe in yourself or your coachees, e.g. isolating, dependency, controlling and demanding behaviours. In this way you might use the model to identify in which direction to look for psychological patterns, edges and issues. At the same time, distinguishing three zones on each axis rather than just two polarities, gives rise to a healthy central space (healthy self-sense and relationship to others), which we can use as an individualised ideal to work towards and strengthen for ourselves or our coachees.

- The model doesn’t recognise the social, cultural or systemic context within which the individual exists. As already suggested, low self-esteem is becoming a systemic societal issue, particularly amongst young people. The pace and stresses of life are making it increasing challenging for all of us to stay centred or grounded, which in part has given rise to the current widespread interest in mindfulness practices. This issue could be explored from a social and systemic perspective, but that is beyond my scope here.

- This is an embryonic model, which needs further development and refinement. I have proposed it because I have not been able to find something suitable elsewhere in the psychological field. I welcome an approach from anyone interested in collaborating to validate and develop the model further.

Much of the personal development work in relationship to the theme of self-sense is about building a stronger centre, an experience of groundedness, an ability to be present to ourselves and others, as well as building greater resilience in the face of life’s difficult situations, unexpected events and unwelcome influences and the emotions these trigger that take us away from our centre and our being. There are many approaches to this of which mindfulness and meditation are currently very popular. The causes of our lack of centre or groundedness can be more deep seated however, and can usefully be explored within the coaching context. Psychosynthesis offers various approaches to working with this at different levels of consciousness and development, including the triphasic model referenced earlier. The practice of disidentification is very important in psychosynthesis as way of building our centre and ground. We can become over-identified with parts of ourselves or the contents of our consciousness and need to work on recognising that this happens and how it affects us and takes us away from our experience of being. Most generally, we can lean towards over-identification with our body, our feelings or our mind (BFM), and then with specific aspects or contents of these. For example in my long term personal development, I have been working on my primary over-identification with mind and my tendency to control my world through thinking. I experienced myself in my head too much of the time and found it hard to stay centred and grounded in my being. When I started my psychosynthesis journey, my personal development goal was the resolution of what I experienced as an essential split between my mind and my heart. I will return to continue with this in an example below.

There is another dimension to our developing sense of self, which is our connection with our higher or transpersonal Self, which we call the I-Self connection in psychosynthesis. As described in the first post on this topic, this is the territory of what Assagioli termed spiritual or transpersonal psychosynthesis and is the second part of our personal development journey (and sadly beyond the scope of this post).

Trauma and personality splits

The above model is a way of considering our psychological health in terms of our generalised relationship with others and with ourselves, that is designed to help the coach recognise the underlying and prevailing personality issues and edges they might be dealing with. We have emphasised that our patterns in relationship to the model (swings between polarities, situational variations, etc.) can be many and varied depending upon other psychological and personality factors, as well as situational and systemic context. A different approach to understanding the personality that helps explain these patterns is to recognise the splits giving rise to different parts in our personalities that have come into existence as a consequence of traumatic experience, particularly in our childhood and early years. Our personality is less a consistent harmonious unity, more a multitude of parts that are reactivated by people and situations and that we may have more or less consciousness and choice about, depending upon our personal development. Psychosynthesis offers the systemic model of subpersonalities as a way of understanding the nature and relationship of different parts of our personality and this will be fully explored in a later chapter on coaching interventions. Here I want to briefly touch upon a different theory of the parts of the personality; Identity-orientated Psycho-Traumatology (IoPT), developed by Professor Franz Ruppert, which is explained in an excellent paper on “What has trauma got to do with coaching? Or coaching got to do with trauma?” by Julia Vaughan Smith (2015).This model shows how splits in the personality and identity structure after a traumatic experience give rise to three parts of ourselves (healthy, traumatised, survival) and Julia explores how to work with these in coaching. She explains how trauma is held in the body and points towards related developments in somatic coaching to help with this.

The key point for coaches in relationship to our personal development is to learn to recognise when we are operating out of our survival part, when a traumatic part is triggered and when we are relating from our healthy part. More often than not, swings between inflation and deflection or an inability to stay centred and grounded, can be linked with the triggering of our survival part and associated subpersonalities that may be in conflict within our psyche.

Above I mentioned my over-identification with mind as a continuing theme in my personal development. This can also be seen as a split in my psyche in my early life, giving rise to the emergence of mind identified survival parts (which I can associate with archetypal subpersonalities such as the critic, teacher, judge, analyst, etc.). As I started to fully recognise this survival part (and thus step outside survival into my healthy part), I suddenly experienced a psychic release and an energetic dropping down into my being. The split between mind and heart was in some alchemical way healed at an essential level and I have been able to draw upon this experience again when needed. I have told this story to illustrate how these different approaches to psychological health and personal development connect up, or can be seen to be tackling the same issues from different perspectives.

Conclusion

That concludes (for now!) this somewhat extended odyssey through the territory of personal development and the models that might be useful to the coach in both working on themselves, as well as increasing their awareness of their coachees issues and challenges. I have deliberately switched between speaking to our own personal development and that of our coachees, because that is how I experience needing to work on our development alongside our practice. We have introduced some important psychosynthesis concepts alongside some of the most common psychological and personality models in use today. We have also spent some time establishing the personal development context that needs to underpin our professional development as a psychosynthesis coach.

Assagioli, Roberto (1965), ‘Psychosynthesis’

Assagioli, Roberto (1974), ‘The Act of Will’, London: Aquarian Press

Bushe, Gervase (2010), ‘Clear Leadership’

Simpson, Steve; Evans, Joan and Evans, Roger (2014): Essays on the Theory and Practice of a Psychospiritual Psychology, Volume 2 (Published by The Institute of Psychosynthesis)

Other sources directly linked